The conceptual phase

Part 1: Preliminary research objective/question and literature review

Plan

- Overview of the conceptual phase

- Choosing a research topic

- Enunciating the preliminary research question

- Reviewing the literature

The conceptual phase

Choosing a research problem and enunciating the preliminary research goal/question (this week).

Reviewing the literature (this week).

Defining the research framework (next week).

Formulating the final research problem (next week).

Formulating the specific research questions or hypotheses (next week).

Defining a research problem and a preliminary research objective/question

Sources of inspiration for research problems

- Your own observations

- Past research

- Social issues

- Theory

- Practical problem

- Organizational priorities

Refining the problem

Three ways of refining the problem:

- Approaching the topic from a specific (often disciplinary) perspective.

- Setting a target population.

- Identifying key concepts.

Approaching the problem from a specific perspective

Example: Alcohol consumption by high school students

- How does alcohol consumption affect academic performance (educational perspective).

- How do teens with high alcohol consumption perceive themselves (psychological perspective).

- How does social group affect the likelihood of high alcohol consumption among teens (sociological perspective).

- How would you approach this problem from a library/informational perspective?

Setting a target population

The population is not necessarily the particular group you will study, it’s the group about which you want to produce knowledge. Example:

- Young adults (very broad)

- University students (broad)

- Undergraduate students (less broad)

- Dalhousie undergraduate students (narrow)

- Undergraduate students in the faculty of Management (narrower)

- Undergraduate students in a specific course (very narrow)

Identifying key concepts

What are the specific concepts that you will be considering in your research? Example:

- Information behaviour?

- Information literacy?

- Access?

- Misinformation?

- Information overload?

Formulating a preliminary research objective/question

This is a high-level, preliminary research question that reflects the main purpose of your research.

Another way to think about this is to separate the research topic, research problem, research goal, and research questions/hypotheses. At this stage, we are defining the research goal (formulated as a question), which will eventually be divided into several specific research questions.

The research question is finalized after the literature review stage.

Relationship between the objective/question and the type of research

Source: (Fortin and Gagnon 2016, 69–70)

Descriptive research

| Question | Goal | State of knowledge | Type of research |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is? What? Who? What is the nature/purpose/meaning of? | Explore, discover, understand phenomena. | Not extensively studied; not fully understood; under theorized. | Qualitative studies |

| What are the characteristics of? What is the prevalence of? | Name, classify, describe, count, measure | Not extensively studied; not fully understood; under theorized. | Quantitative studies |

Explanatory research

| Question | Goal | State of knowledge | Type of research |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the relation? What are the associated factors? What is the process? | Explore, discover, understand phenomena. | Not extensively studied; not fully understood; under theorized. | Descriptive-correlational studies, time series studies. |

| What is the influence/contribution? Why? | Explain the direction and strength of relationships. Test hypotheses | Existing publications support the existence of the relationship. Theories and models. | Correlational-predictive studies; cohort studies; case-control studies |

Predictive research

| Question | Goal | State of knowledge | Type of research |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the effect of? What are the differences between groups? How effective is? | Predict causality, establishing group differences. | Well-researched phenomenon; Existing theory(ies)/model(s). | Experimental or quasi-experimental studies |

Examples

“we examine how factors related to the tweeter (e.g., academic age, research activity, tweeting activity) and the relationship between the tweeter and the tweeted works (e.g., shared field, authors, or geographical location) may affect the probability that a researcher tweeting a paper will also cite that same paper.” (Hare et al. 2024)

“This paper […] investigat[es] the coverage of gold and diamond journals in WoS and Scopus. Additionally, we seek to determine whether there is empirical support for the narrative that diamond journals are more community-driven and local in nature by analyzing the geographical and linguistic characteristics of gold and diamond journals and their relation to WoS and Scopus coverage. Further, it examines the characteristics of indexed diamond journals, such as country of publication, geographic concentration of authors, to produce a fuller portrait and subsequent understanding of how and why publications are represented in bibliometric databases. (Simard et al., n.d.)

“This paper aims to provide empirical evidence of the extent of English/Anglophone LIS scholarship that includes race and/or racial inequity as an area of focus.” (Mongeon et al. 2021)

“We leverage detailed information on more than 2,000 applications to the Villum Foundation’s Villum Experiment”, a double-blinded grant scheme, to evaluate how blinding can reduce gender bias in research funding.” (Madsen, Mongeon, and Schneider, n.d.)

“In response to these calls, we surveyed Canadian environmental researchers’ perceived capability to conduct and disseminate research to inform decision-making and engage in effective knowledge mobilization.” (Robertson et al. 2023)

“The purpose of this study is to empirically explore the relative contribution of primary authors, middle authors and supervisory authors to research articles in the biomedical field.” (Mongeon et al. 2017)

“Drawing on the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (Association of College & Research Libraries, 2015) and the DigComp framework (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2022), the study focuses on four groups of digital skills: information literacy, data literacy, visual literacy, and communication and collaboration. The study examines the differences between these four sets of digital literacy skills, which constitute student learning outcomes for higher education (Sparks et al., 2016), and their relationship to the self-assessment of psychological empowerment among recent graduates employed in the business services sector (BSS).” (Deja et al. 2024)

“The aim of this paper is to explore how games, such as The Euphorigen Investigation, can support misinformation education when viewed through the sociocultural perspective, emphasizing the everyday practice and cultural context of literacy as opposed to a set of cognitive skills” (Wedlake, Coward, and Lee 2024)

“This study aims to explore the potential impact of scientific information disseminated on social media on public health.” (Quan and Zhang 2024)

“Our analysis provides a detailed understanding of how and why various information behaviors contribute to view change and foregrounds a tight symbiotic relationship between HIB and view change, where HIB not only drives and view change but is also driven by it” (McKay et al. 2024)

“Elaborating on the CTI [communication theory of identity] prism, this study attempted to elucidate users’ identities in OHCs [online health communities] from the relationship-layer perspective, thus showing how their relationship-layer identities evolve and interact with users’ personal-layer identities.” (Chen et al. 2024)

“We sought to find the relationship between curiosity and awe by creating short, immersive experiences using videos that exemplified awe.” (Urban and Bossaller 2024)

Characteristics of a good research objective/question

Relevant: the research goal is of interest to the target audience.

Significant: fulfilling the research goal would significantly advance knowledge.

Feasible: the research goal is possible and likely to be achieved.

Related to theory: the research goal implicitly or explicitly draws from and/or contributes to theory.

Literature review

Purpose

Establish the state of knowledge (to help identify the gaps).

Define and delineate the research problem.

Identify the key concepts.

Gain methodological insights.

Learn from the results, limitations, and recommendations of past studies.

Position your research within the existing literature.

Gives credibility to your work.

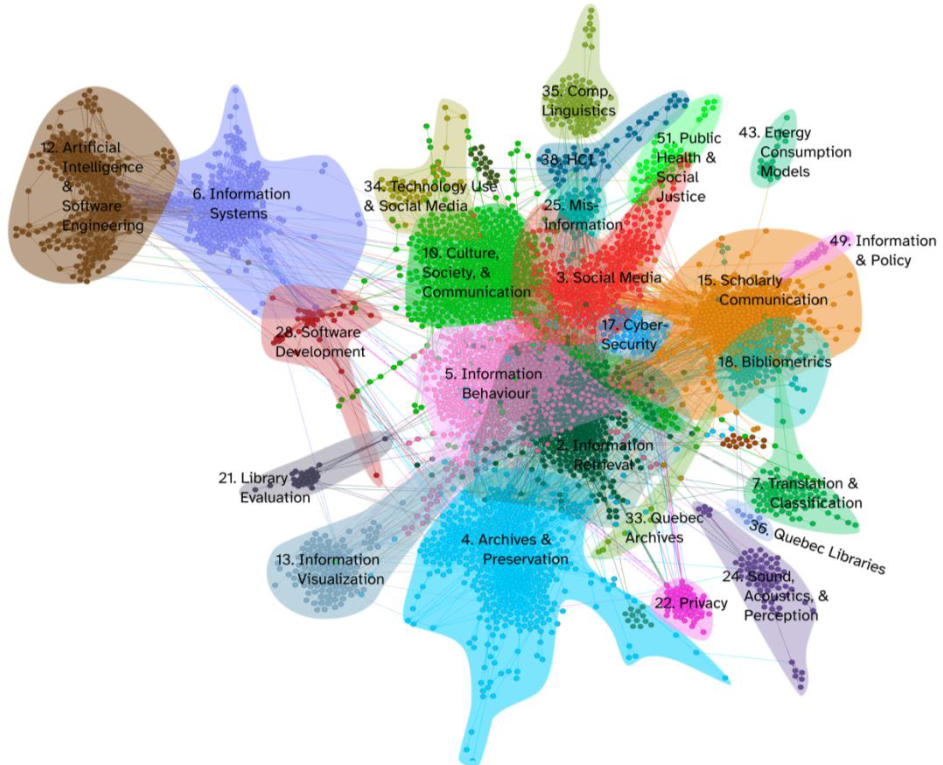

Example: map of the LIS literature

Information sources

Empirical sources: publications that report results of empirical studies.

Theoretical sources: publications that present concepts, models, theories, or conceptual frameworks.

Primary sources: report of study by the researcher(s) who conducted it.

Secondary sources: synthesis, summary, or commentary on a work by someone other than the author of the original work (e.g., textbook, encyclopedia, reviews, annotated bibliography)

Process overview

- Define search strategy

- Select sources

- Implement search strategy (perform the search)

- Identify relevant literature

- Critically appraise the selected literature

- Synthesize the selected literature

Defining search strategy

- Identify the core concepts that constitute your research problem.

- For each concept, identify synonyms and other terms that could retrieve literature associated with each related term.

- Most of you are likely familiar with the literature search process, but if not, you can check out the Zombool game.

Selecting sources

Where are you going to search for information, for example:

- Library catalogue

- Specialized or multidisciplinary database

- Internet

Implementing the search strategy

Basically, the search is run in the selected database(s).

Determine relevancy

At this stage, the goal is to determine what the retrieved publications are about and filter out the ones that are not relevant to your study.

Key data points: the title, the abstract, and the research objectives.

Consider creating a screening spreadsheet with three columns:

- Title

- Year

- Source (e.g. journal)

- Abstract

- Research objectives

Critically appraise the selected literature

Once you identified relevant sources, your next step is assessing their quality. Here are some criteria to consider:

- Is the research problem and objective clear?

- Is it relevant and significant for the field?

- Is the literature review present and adequate?

- Are the concepts defined? Is the theoretical framework explicit and justified?

- Are the research questions clearly enunciated?

- Is the population described?

- Are the methods clearly described?

- Is the method suited to the research objectives?

- Is the research ethically conducted?

- Are the results clearly presented?

- Are the visualizations (tables, graphs) helpful?

- Are the results adequately interpreted and related to the past literature?

- Are the limitations of the study described?

- Are the conclusions supported by the data and results?

Synthesize the selected literature

At this stage, you could, in principle, start writing your literature review.

- Extract and synthesize useful information from the literature.

- Best to have a plan or to build one along the way!

- You can also synthesize articles individually and integrate them later.

Repeat until saturation

Use what you’ve learned in the first round of the literature review to:

- Refine your search strategy.

- Try to fill gaps in the literature review.

- Find additional relevant sources using other methods, such as:

- Citation tracking from core sources.

- Look up the Google Scholar profile of core authors identified in your reviews.

Examples of literature review

Structured literature reviews (with headings delineating the different aspects covered).

Articles that don’t have a distinct literature review section (the literature review is implicit and embedded in the introduction.